Thanks to a social media post by Baddredin Mukhtar I came across a source previously unknown to me: the Swedish diplomat Jacob Gråberg’s eyewitness account of the Austrian siege of French-occupied Genoa in 1800. Apparently published in Tripoli in 1828, it is certainly one of the oldest books printed in Libya. Though it is quite hard to know if it is the oldest, it is, as Mukhtar proposes, so far the oldest we have a clear evidence for.

Gråberg (1776–1847) was a Swedish scholar and diplomat who served as consul in Tripoli from 1823 to 1828, and had previously held positions in Genoa and Tangiers. He observed and wrote copiously throughout his travels, for example, a report on the 1818 plague epidemic in Morocco or notes on the language of Ghadames.

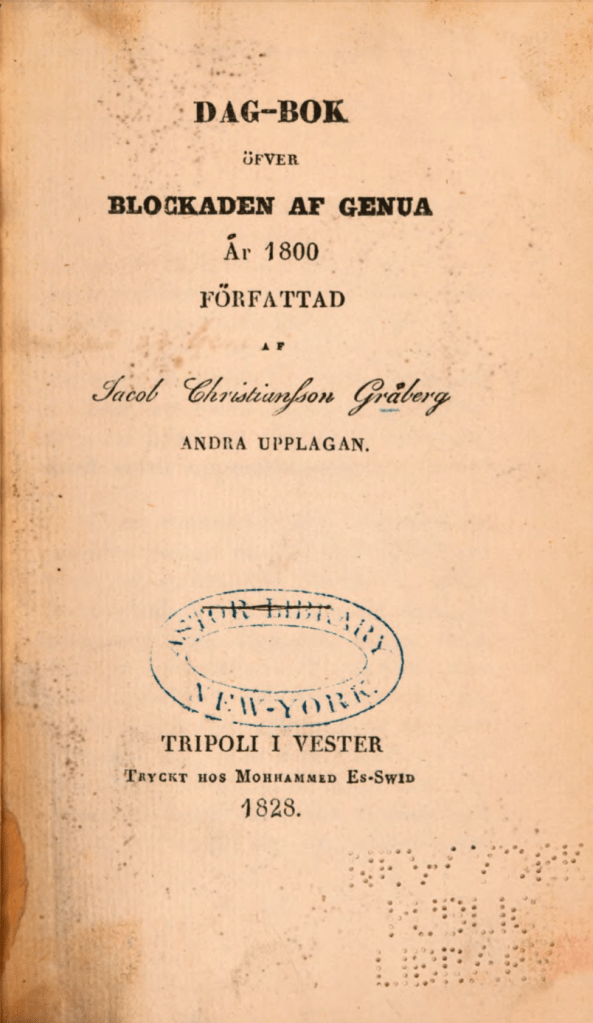

The book in question, Dag-bok öfver blockaden af Genua år 1800 (Diary on the Siege of Genoa in 1800), was published in 1828 at the press of Mohhammed Es-Swid in “Tripoli I Vester”, that is, Trâblus Gârb (طرابلس الغرب) in Ottoman nomenclature.

The contents have nothing to do with “Tripoli I Vester” at all, but rather are Gråberg’s observations of the Austrian siege of French-occupied Genoa in spring and summer 1800, when he was an officer in the Genoa National Guard after having held bureaucratic roles at the Swedish mission in the then-Ligurian Republic. It seems he only got around to publishing them almost three decades later, and published them wherever he was at the time—in this case, Tripoli—as he did with many of his other writings. The diary was later, in the 1890s, translated into Italian by a historian of Liguria (G. Roberti, “Due diari inediti dell’assedio di Genova nel MDCCC”, Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria, 1890 No. XXIII).

As for the press itself, so far I know nothing about “Mohhammed Es-Swid”. It bears remarking that during this period European/Christian converts to Islam, whether as hostages, or conscripts, or other, often simply took (or were referred to using) their country of origin as a family name—e.g. the notable and still extant Libyan family الصويد, which may well be connected with the Mohhammed Es-Swid of our early 19th-century press.

But whether his press printed any other books is not known, and so Gråberg’s Genoese diary may or may not have been the first. Still, I know of no Ottoman or Jewish press operating in Tripoli at this time. The Ottoman newspapers published in Libya got started a bit later, around the mid-1800s. A French newspaper (called المنقب الافريقي) was apparently published in Tripoli in 1827, although I can find no real information about it so far. Jewish presses, publishing both religious texts and newspapers, seem to have gotten going around the end of the 19th century (e.g. the houses of Abraham Tesciuba, Clementi Zard, or Solomon Tesciuba that continued into the colonial period); earlier, the Jewish community seems to have printed predominantly in Livorno or other locations outside of what is now Libya.

More information would be appreciated!