A dossier entitled “Responding to Invasion: Afro-Asian Reactions to the Italo- Ottoman War, 1911-1912” edited by Carlotta Marchi and Massimo Zaccaria has appeared in the journal Africa. Rivista semestrale di Studi e Ricerche (VI/2, 2024). The dossier’s abstract states:

This dossier provides a comprehensive examination of the social, cultural, and material consequences of the Italo-Ottoman War (1911–1912) within a global historiographical perspective. It explores how the Italian invasion of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica sparked widespread solidarity across non-European regions. While the historiography of the conflict has hitherto focused on its European ramifications, this dossier investigates the unexplored reactions from non-European societies, particularly in those regions connected to the Ottoman Empire, such as North Africa, the Horn of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Indian Ocean. The articles examine global opinion and transnational networks of anti-imperialist and pan-Islamist activists, as well as alternative perspectives supporting Italy. By conducting such an analysis, the articles unveil intricate dynamics that supersede the conventional colonial dichotomy, emphasising collaborative endeavours and mediation initiatives.

Articles

Vanda Wilcox, “Towards a Global History of the Italo-Ottoman War”

Though often overshadowed by the events of the First World War, the Italo- Ottoman War deserves closer attention. Its study might be revitalized by drawing on recent historiographical trends within First World War studies, which emphasize both global perspective and a re- evaluation of chronological boundaries. Future studies might also draw on diverse methodological approaches, including military, social, political, and cultural histories, to deepen our understanding of the war’s multifaceted dimensions. The fields of African and colonial history can suggest further possible future avenues of approach, as can the Second Italo- Ethiopian War. The article calls for a nuanced re-evaluation of the Italo-Ottoman War that transcends Eurocentric perspectives and acknowledges its significance as a pivotal moment in global history, and concludes with a short evaluation of the war’s impact in British India.

Carlotta Marchi, “‘Arab Voices’: Press, Public Opinion and the Intellectual Response in Egypt on the Italo-Ottoman War”

During the Italo-Ottoman conflict of 1911-1912, Egypt played an important moral and material role. It was the scene of a series of manifestations and reactions of solidarity that took place in the press, in public opinion, and in literary and intellectual production. This response reflected the circulation of shared sentiments and ideals, of which Egypt became one of the centres of reference, based on a tangible trans-colonial perspective. In this sense, this paper aims to analyse the construction of awareness of the Italo-Ottoman war in Egypt, focusing on the role of “Arab voices” in promting a common sense of Ottoman, Arab and Islamic identity and solidarity, and a shared critique of Western “civilisation”. The study of newspapers, poems, discourses, reactions, and their impact and circulation favour a broader analysis of the expansion of anti-colonial solidarity, both geographically and temporally.

Massimo Zaccaria, “Courting African Public Opinion: Echoes of the Italo-Ottoman War along the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean”

The Italo-Ottoman war played an important role in mobilising public opinion. In the Americas as well as in Asia, the war aroused a great deal of participation, generated polemics and protests and, to a much lesser extent, gathered support. The study of the reactions to the Italian aggression in Africa has mainly concerned the northern part of the continent. Sub-Saharan Africa remains the great absentee, implicitly conveying the message that this region’s involvement in the conflict was minimal. Indeed, the area was not short of reactions, but one has to use the right sources and look beyond the newspapers. This is the only way to understand the profound impact that the war between Italy and the Ottoman Empire had on the Horn of Africa. Reactions were not clear-cut: the article explains why Pan-Islamism was not the only option available and why in some areas the Ottoman appeal was deliberately ignored.

Çiğdem Oğuz, “Beyond the Nationalist Propaganda: Rethinking Ottoman Literary Production on the Italo-Ottoman War of 1911”

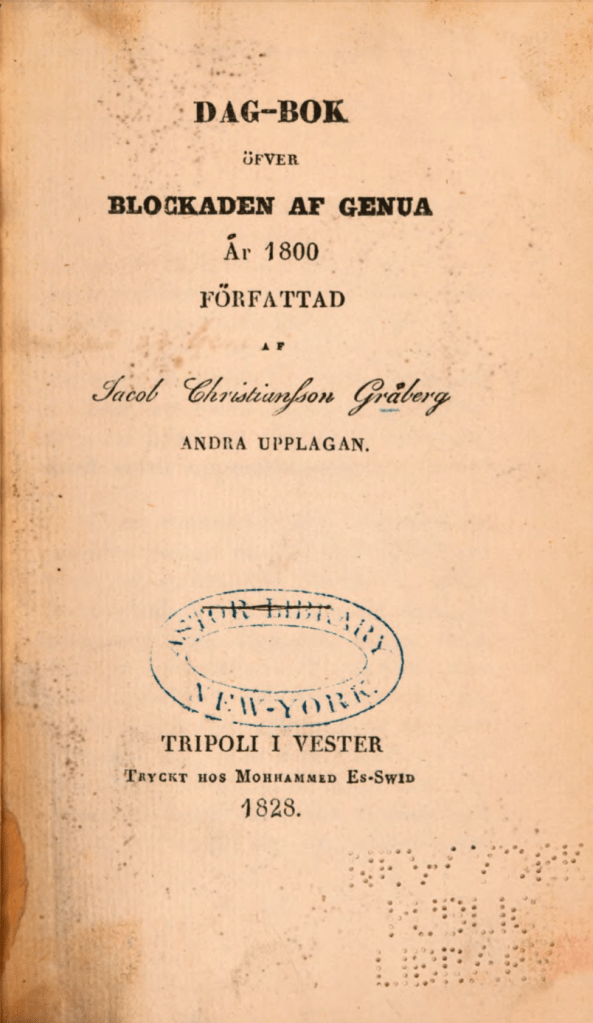

As the last African territory of the Ottoman Empire, Tripolitania was of great importance to the Ottoman government in maintaining its prestige in the Muslim-Arab world. This paper examines the short stories mostly published in the new genre of “national literature” at the time of the Italo-Ottoman War of 1911. The stories provide insights into Ottoman-Turkish perspectives on Turkish-Arab solidarity, especially around the figure of the Caliph, as an Ottomanist strategy. While most of the stories aimed to illustrate the economic and social struggles of the empire and to evoke a sense of voluntarism to save the crumbling empire, they also served the practical purpose of responding to Italian claims of a “civilizing mission” that reduced the Ottoman Empire to colonial status, despite its recent attempt at political reform in 1908 with the Young Turk Revolution.

Silvia Pin, “The Reaction to the Italo-Ottoman War in the Hebrew Press of Jerusalem: A Reading of the Newspapers Ha-’Or and Ha-Ḥerut, October-November 1911″

The Italo-Ottoman war of 1911-1912 sparked bitter reactions in the contemporary press across the Ottoman Empire, as well as indignation and mobilisation against Italy. Amongst the Ottoman press, the Hebrew language newspapers of Jerusalem broadly covered the war, providing local Jewish perspectives on this much-debated event. This article aims to analyse the initial press coverage of the Italo-Ottoman war in two Zionist Hebrew-language newspapers of Jerusalem, the Ashkenazi Ha-’Or and the Sephardi Ha-Ḥerut. In the first months of war, the two Hebrew journals strongly though with some contradictions condemned the Italian invasion of Tripolitania, professed – and promoted – Jewish loyalty to the Empire and in so doing defended the harmless ends of Zionism. They denied that Jews in Tripoli supported the Italians and, in covering pro-Ottoman demonstrations in and out of Palestine, notably in Egypt, Ha-Ḥerut also took note of a burgeoning pan-Islamic sentiment triggered as a reaction to the Italian assault.