Jihan Kikhia’s long-awaited documentary film “My Father and Qaddafi” about her father Mansur Kikhia’s forced disappearance by the Qaddafi regime in 1990s is now out. Its international debut will be at the Venice Biennale this month.

The disappearances and assasinations of the 80s and 90s, and indeed the Libyan opposition movements to the Qaddafi regime, are some aspects of Libyan history that are poorly known and understood by non-Libyans (despite even the success of Hisham Matar’s book The Return, for example), and even increasingly by younger generations of Libyans. As Kikhia notes in her director’s statement, “this is one of the ways I am hoping to hold my father before he disappears completely from my memory and even potentially from Libya’s memory.” This film is an important addition to Libyan history and joins a short list of beautiful and insightful documentaries about Libyan topics from the last few years, including Khalid Shamis’ thematically-related “The Colonel’s Stray Dogs”.

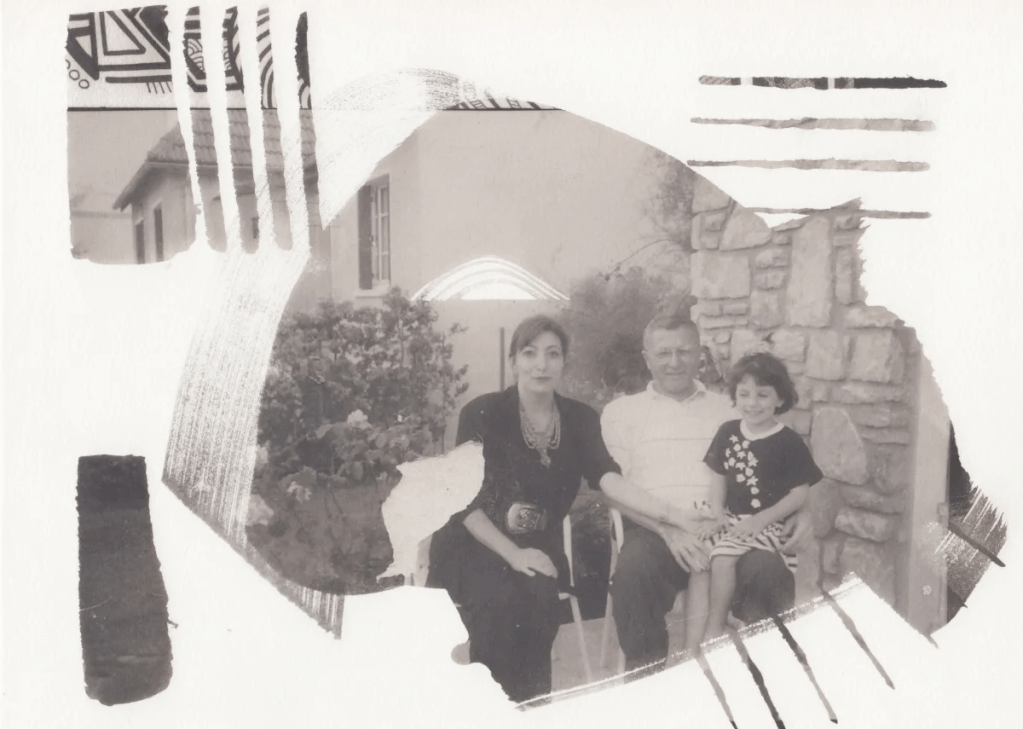

Synopsis: In My Father and Qaddafi Jihan K pieces together a father she barely remembers — Mansur Rashid Kikhia was a human rights lawyer, Libya’s foreign minister and ambassador to the United Nations. After serving in Qaddafi’s increasingly brutal regime, he defected from the government and became a peaceful opposition leader. For many, Kikhia was a rising star who could replace Qaddafi, however, in 1993 he disappeared from his hotel in Egypt. Jihan’s mother, Baha Al Omary, searched for him for nineteen years until his body was found in a freezer near Qaddafi’s palace.

Through encounters with family, her father’s colleagues, and historical archives, Jihan’s search for the truth evolves into a deeper curiosity, drawing her closer to both her father and her Libyan identity.

View the trailer here: