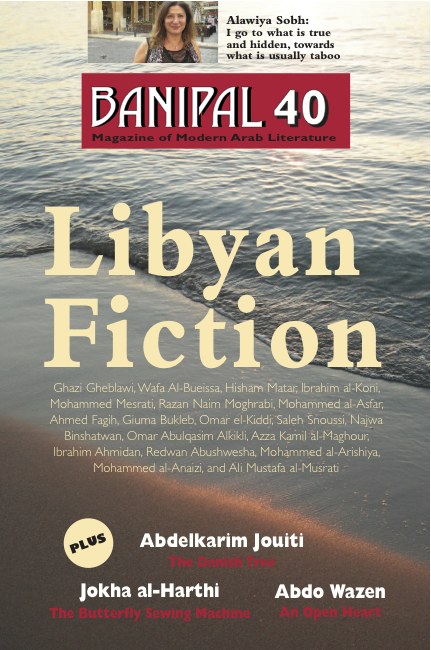

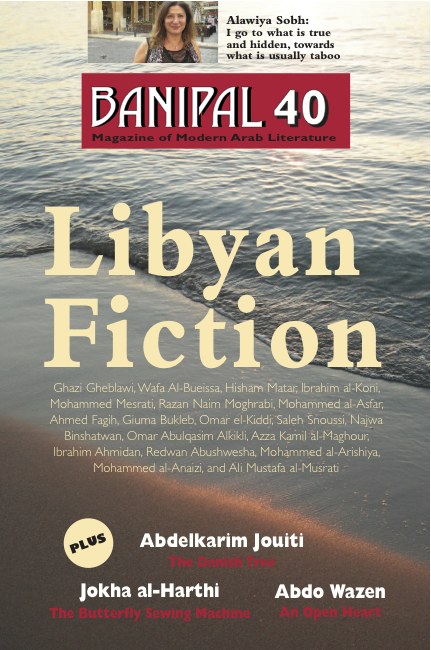

Banipal, the UK-based magazine of modern Arabic literature in English translation, published an issue dedicated to Libyan Fiction back in 2011. The print edition is reasonably priced and well worth having, but issue 40 also happens to be available online at Banipal’s website! You can read every piece of Libyan fiction in the issue for free. Together with the recent second edition of Ethan Chorin’s Translating Libya (see here), it represents the best and most recent collection of Libyan literature in English translation, and both are absolutely essential introductions to many of today’s important writers.

Banipal, the UK-based magazine of modern Arabic literature in English translation, published an issue dedicated to Libyan Fiction back in 2011. The print edition is reasonably priced and well worth having, but issue 40 also happens to be available online at Banipal’s website! You can read every piece of Libyan fiction in the issue for free. Together with the recent second edition of Ethan Chorin’s Translating Libya (see here), it represents the best and most recent collection of Libyan literature in English translation, and both are absolutely essential introductions to many of today’s important writers.

From the editor’s description of the issue:

“What an amazing coincidence that [Banipal’s 40th issue] should be dedicated to the celebration of Libyan literature at such an extraordinary historical moment in the Arab world when the region is witnessing a chain of uprisings and revolutions against dictatorial and corrupt regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen and, finally, Libya.

We at Banipal are very proud of this special issue on Libyan fiction, and with it announce our absolute solidarity with the Libyan people in their aspiration to democratic rule and the exercising of all their rights, the first of which are to express their thoughts and the abolition of all forms of censorship on audio-visual media and literature.

When I met by chance the veteran Libyan writer Ali Mustafa al-Musrati, one evening at the Greek Club in Cairo, February 2007 (at this time exactly), I said to him: “I’m extremely saddened by the neglect of Libyan literature in the Arab world and by the ignorance of the West.” I promised him that Banipal would publish a special feature on the wonderful literature of Libya. And how happy we are to fulfil this promise at this time in particular…”

The Libyan authors whose work appears are (in no particular order): Ghazi Gheblawi, Wafa al-Bueissa, Hisham Matar, Ibrahim al-Koni, Mohammed Mesrati, Razan Naim Moghrabi, Mohammed al-Asfar, Ahmed Fagih, Giuma Bukleb, Omar el-Kiddi, Saleh Snoussi, Najwa Binshatwan, Omar Abulqasim Alkikli, Azza Kamil al-Maghour, Ibrahim Ahmidan, Redwan Abushwesha, Mohammed al-Arishiya, Mohammed al-Anaizi. There is also profile on Ali Mustafa al-Musrati.

Anna Baldinetti,

Anna Baldinetti,  Banipal, the UK-based magazine of modern Arabic literature in English translation, published an issue dedicated to Libyan Fiction back in 2011. The print edition is reasonably priced and well worth having, but issue 40 also happens to be available online at

Banipal, the UK-based magazine of modern Arabic literature in English translation, published an issue dedicated to Libyan Fiction back in 2011. The print edition is reasonably priced and well worth having, but issue 40 also happens to be available online at

I recently came across a small, old pamphlet entitled, in French, “

I recently came across a small, old pamphlet entitled, in French, “