Ravelli, Galadriel. 2024. Libyan deportees on the Italian island of Ustica: Remembering colonial deportations in the (peripheral) metropole. Memory Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/17506980231224759.

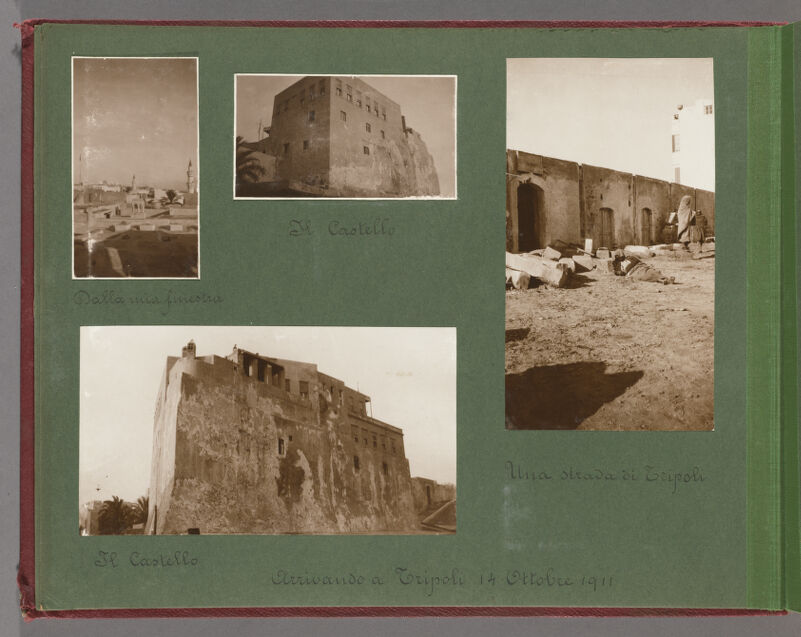

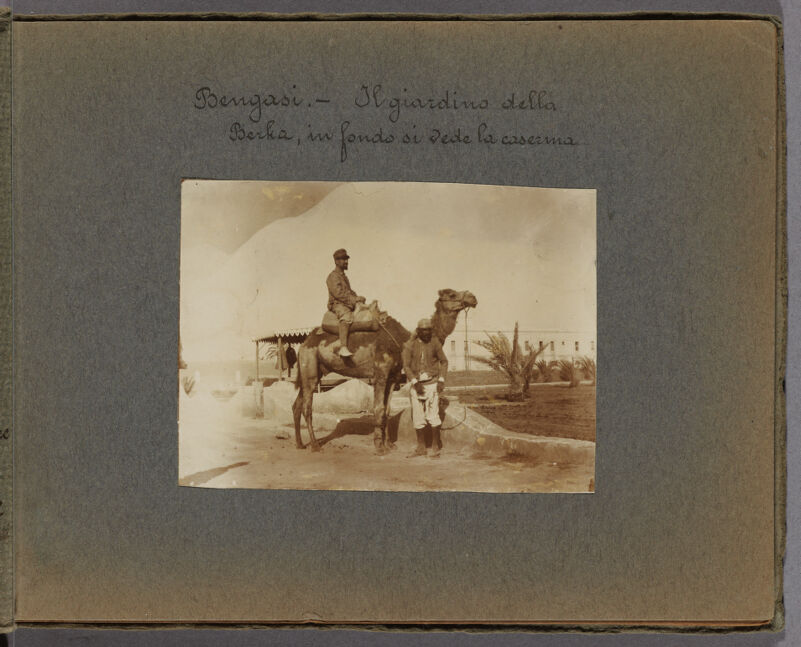

In 1911, the Italian liberal government launched the colonial occupation of what is now known as Libya, which was met with unexpected local resistance. The government resorted to mass deportations to the metropole to sedate the resistance, which continued for more than two decades under both the liberal and Fascist regimes. This chapter of Europe’s and Italy’s colonial history has been almost entirely removed from collective memory. The article explores the extent to which colonial deportations are remembered on the Sicilian Island of Ustica, which witnessed the deportation from Libya of more than 2000 people. Currently, the island is home to the only cemetery in Italy that is entirely dedicated to Libyan deportees. I argue that the visits of Libyan delegations, which took place from the late 1980s to 2010, succeeded in challenging colonial aphasia at the local level. Yet, as a result of Ustica’s peripheral position within the national space, the memory work developed through the encounter between local and Libyan actors remained marginal, despite its potential to redefine the Mediterranean as a symbolic space where colonial histories are articulated and remembered. Italy’s outsourcing of the memory work in relation to colonial deportations implies a missed opportunity to interrogate the postcolonial present and thus question persistent dynamics of power in Europe that exclude the constructed Other.

Morone, Antonio M. 2024. The Libyan askaris on the eve of national independence: two life stories across different strategies of intermediation. The Journal of North African Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2024.2360911.

Italian colonial authorities heavily relied on the askaris (i.e. native soldiers) throughout the history of colonialism to alleviate the economic and political burdens of colonial warfare. For that, the askaris became privileged intermediaries for the Italians and emerged as a de facto elite within colonial society, seeking social mobility for themselves and their families. After the end of the Second World War, the askaris lost their role as soldiers, but gained new relevance as political intermediaries for Italian or British plans regarding the final resolution of the Italian colonies affaire. The article delves into the life stories of two askaris, which were documented by the author on 3rd November 2009, in Tripoli. Their memories highlight the relationships of friendship or intimacy that existed with the colonisers and showcase the askaris’ ability to downplay colonial elements of domination and oppression through their intermediation. Being an askar entailed, on one hand, questioning the political and racial boundaries of society, and on the other hand, challenging the agendas of nationalist groups. The transition to independence indeed involved a struggle between colonisers and the colonised, as well as among various groups of colonial subjects, all vying for power within the post-colonial State and society.

Tarchi, Andrea. 2022. A ‘catastrophic consequence’: Fascism’s debate on the legal status of Libyans and the issue of mixed marriages (1938–1939). Postcolonial Studies 25(4). 527–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2021.1964764.

This article assesses the role that institutional concern for the possibility of interracial marriages played in the Italian Fascist party’s internal debate regarding the legal status of Libyans in the second half of the 1930s. Following the end of the ‘pacification’ of the Libyan resistance in 1932, Governor Italo Balbo pushed for the region’s demographic colonization and the legal inclusion of the colonial territory and its population within the metropole. In contrast, Fascist Party officials in Rome endorsed starker racial segregation in the colonies based on the racist ideology that permeated the regime after the declaration of the empire in 1936. The legal inclusion of Libyans within the metropolitan body politic touched upon the regime’s most sensitive theme: the need to avoid any promiscuity that could interfere with the racial consciousness of Fascist Italy. This article analyses this dispute through the lens of interracial marriage and concubinage regulations, framing it into the definition of a normative standard of Italian whiteness through the racialization of the colonial Other.

Rossetto, Piera. 2023. ‘We Were all Italian!’: The construction of a ‘sense of Italianness’ among Jews from Libya (1920s–1960s). History and Anthropology 34(3). 409–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2020.1848821.

The paper explores how a ‘sense of Italianness’ formed among Jews in Libya during the Italian colonial period and in the decades following its formal end. Based on interviews with Jews born in Libya to different generations and currently living in Israel and Europe, the essay considers the concrete declensions of this socio-cultural phenomenon and the different meanings that the respondents ascribe to it. Meanings span from the macro level of historical events and societal changes, to the micro level of individual social relations and material culture. Viewed across generations and framed in the peculiarities of Italian colonial history, the ‘sense of Italianness’ expressed by Jews in Libya appears as both a colonial and post-colonial legacy.